Jinko and the Art of Kōdō

In Japan, Oudh is referred to as “Jinko” (沈香), and its presence is deeply rooted in various cultural and spiritual practices. Jinko is often associated with the ancient art of Kōdō, the “Way of Incense.” Kōdō is a traditional Japanese art form that focuses on the appreciation of incense, and it holds a profound place in Japanese culture.

Kodo, or the “Way of Fragrance/Incense,” is one of the three major classical arts that every refined individual was traditionally encouraged to master, alongside sado (the tea ceremony) and kado (flower arrangement).

While Kodo may be the lesser-known among the trio, its modern counterpart, aromatherapy, has gained significant popularity in recent times, showcasing the enduring influence of the fragrance arts in contemporary wellness and relaxation practices.

Together with sado (tea ceremony) and Kado (flower arrangement), Kodo (incense ceremony) ranks as one of the classic arts of Japan cultivated by members of the aristocracy as a refined hobby.

In Kōdō, participants engage in the precise ritual of smelling incense and appreciating its various aspects, from its aroma to its packaging. Oudh is highly regarded in this practice for its intricate scent and depth. In Kōdō, the appreciation of Oudh goes beyond the olfactory; it represents an intimate connection with nature and an avenue for mindfulness.

The fragrance of Oudh, also known as The Fragrance of Legends, has enchanted the senses of people across the globe for centuries. This fragrant elixir is derived from the resinous wood of the Aquilaria malaccensis Lam tree (agarwood), prized for its rich, complex, and enduring aroma. Its significance transcends borders, particularly in Asian cultures like Japan and China, where Oudh is interwoven with traditions, spirituality, and daily life.

The Roots of Kodo, “Incense Ceremony”, and Its Evolution

Kodo, the “Way of Fragrance,” is a practice deeply rooted in Japanese culture, tracing its origins back to the Nara Period (710-794). It began with the use of fragrant woods in Buddhist rituals, emphasizing the sacred connection between scent and spirituality.

As naturally scented wood is a rarity, the evolution of man-made incense became essential to the continuity of this practice. This fragrant art found its formalization around the time of Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1443-1490), a shogun who tasked the scholar Sanjonishi Sanetaka with classifying the incense of the era, thus earning Sanjonishi the revered title of the “father” of Kodo.

This incense, similar to what is used in Christian churches, was believed to possess purifying properties, a notion that continues today, as it is employed to purify wooden memorial tablets offered to the deceased during funerals. Smoldering incense sticks, known as “senko,” find a regular place on gravestones and within “butsudan,” small altars commonly found in Japanese homes.

Nara Daibutsu – in Todaiji Temple in the Daibutsuden

Oudh, The Precious Resinous Wood

Oudh, the aromatic jewel derived from the resinous wood of the Aquilaria or agarwood tree, seamlessly integrates with Kodo’s rich history.

Oudh’s complex and enduring fragrance aligns with the spiritual and meditative aspects of Kodo, making it an invaluable addition to this olfactory art form.

The mesmerizing scent of Oudh, known for its grounding and transformative properties, enhances the sensory experience, allowing practitioners to delve deeper into the art of fragrance appreciation.

Thus, the use of Oudh in Kodo exemplifies the enduring and harmonious connection between scent, tradition, and spiritual enrichment.

Oudh – Resinous Agarwood Chips

The formalization of Kodo occurred around the time of Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1443-1490), a shogun who tasked scholar Sanjonishi Sanetaka with the classification of incense used at the time. This historical role designates Sanjonishi as the revered “father” of Kodo.

👉Read More: Oudh - The Priceless Fragrance of Legends

Kodo – “way of the fragrance”

Kodo, the ancient Japanese art of appreciating fragrance, classifies scents around the 15th century, with the establishment of a formalized “way/art” of the Incense by founder Sanjonishi Sanetaka (1455-1537 AD), a noble under the Muromachi Shogunate of Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa.

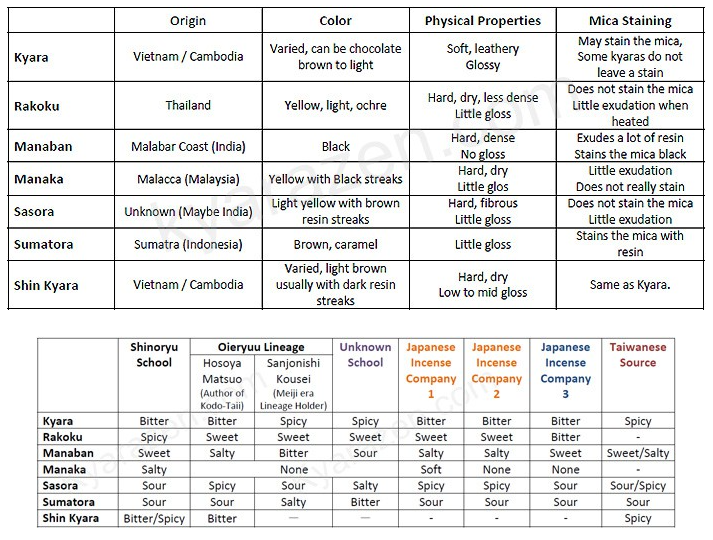

This was method of classification and rating is to “rikkoku gomi,” which translates to “six countries and five tastes.”

Rikkoku Gomi - "Six Countries, Five Tastes"

Rikkoku Gomi, translating to "six countries, five tastes," is a quintessential aspect of Kodo, the Japanese art of appreciating incense. It artfully combines six fragrant woods and embodies five distinct tastes, creating a sensory journey that captures the essence of this ancient practice. The harmonious blend of these elements results in a rich, multi-dimensional olfactory experience, inviting enthusiasts to explore the intricate nuances of each fragrance.

Classification System

Rikkoku profiles – source: https://www.kyarazen.com/perspectives-on-the-rikkoku-gomi/

Six Sources

- Kyara – A solemn and complex scent, usually accompanied by bitterness.

- Rakoku – A sharp scent, which smells sort of like a deeper and wetter sandalwood.

- Manaka – A unique scent. Light and airy in nature. None of the five elements are easily detectable in this type of agarwood.

- Manaban – A sweet scent. Manaban typically has quite a bit of oil.

- Sumotara – An initially sour scent, but it tends to alternate between sour and bitter. Sometimes mistaken for Kyara.

- Sasora – A cooling, slightly sour scent. Quality and scent can vary quite a bit on this one.

Five Tastes of Agarwood

- Sweet – Has a sweet smell, reminding one of honey.

- Sour – Has a sour and acidic smell, reminding one of dark fruit.

- Hot – Has a warming vibe, reminding one of heat, or the color orange.

- Salty – Has a salty, oceanic scent, reminding one of ocean water and a cool wind.

- Bitter – Has a bitter scent. This is the scent which your typical Vietnamese agarwood will have.

Factors Affecting Scent/Taste

Our unique genetic makeup influences the expression of olfactory receptor types. Variations in receptor population and type mean that the olfactory profile of specific scents triggers a different response in individuals with differing genetic profiles.

The exquisite Mon-koh grade woods in high-grade Rikkoku sets undergo multiple phases when heated the Ko-do way. For instance, Rakoku may initially present a bitter note, but it gradually evolves into a delightful sweetness. Consequently, it’s inadequate to categorize each Rikkoku wood by a single taste, especially when dealing with high-grade specimens. Instead, a comprehensive description should encompass the scent profiles and tastes throughout different phases, along with the mental imagery evoked.

One must recognize that the boundaries we assign to countries are human constructs. Plants, trees, and forests do not inherently distinguish themselves by origin. As a result, aloeswoods originating from a single country (koku) may exhibit varied scents. The line between, for instance, Cambodian and Vietnamese woods can blur, particularly among high-quality, wild-harvested specimens known for their sweet and cool profiles.

Additionally, within a single forest, factors like infection mechanisms, tree age, and species diversity lead to agarwoods with distinct aromas. For example, Vietnam yields high-quality agarwoods that may encompass both spicy and sweet notes, while Indonesia, although not a part of the traditional Rikkoku, produces agarwood with an array of tastes. This complexity extends to other agarwood-producing countries, with tastes not completely confined to the five traditional categories.

Kodo Virtues

Since the Muromachi Period (1336-1573), kodo has been associated with ten physical and psychological benefits or virtues:

- Heightening the senses.

- Purifying the mind and body.

- Eliminating mental and spiritual “pollutants” (kegare).

- Enhancing alertness.

- Easing feelings of loneliness.

- Fostering harmony, even in stressful situations.

- Offering a non-overwhelming presence, even when abundant.

- Satisfying, even in small quantities.

- Resisting decay, enduring over centuries.

- Causing no harm, even when used daily.

Taoism and Oudh: An Aromatic Connection

Oudh also finds its place in Taoism, a spiritual and philosophical tradition that has deep roots in China. In Taoism, balance and harmony with nature are essential, and fragrances like Oudh are seen as a means to connect with the natural world. The gentle, grounding scent of Oudh aligns with the Taoist principles of simplicity and serenity.

In Taoist ceremonies and rituals, incense plays a vital role in creating a sacred atmosphere. Oudh, with its calming and transformative fragrance, is often a favored choice. It’s believed to help elevate the spirit and facilitate deeper states of meditation and contemplation.

Oudh in China: A Timeless Symbol of Luxury

In China, Oudh, or “Chénxiāng” (沉香), has a long and illustrious history. It’s often considered a luxurious and exotic fragrance, with a scent profile that’s both woody and sweet. Oudh has been used in various forms, including incense, perfumes, and traditional medicine, for over a millennium.

For centuries, Oudh has been a symbol of luxury and refinement in Chinese culture. It’s used not only for its captivating scent but also for its perceived medicinal properties. In traditional Chinese medicine, Oudh is believed to have numerous health benefits, from soothing digestive ailments to promoting general wellness. It’s also highly sought after as an essential ingredient in high-end perfumes and incense.

Oudh in Other Asian Cultural Activities

Beyond China and Japan, Oudh features prominently in various Asian cultural activities. In India, for instance, it’s used in traditional Ayurvedic medicine and as an essential element in many religious and spiritual rituals. The rich and complex scent of Oudh is believed to purify and uplift the spirit during ceremonies and meditation.

In the Arab world, Oudh is renowned for its use in perfumes and incense. It’s considered an embodiment of luxury and refinement, often used during special occasions and as a mark of distinction.

Oudh in Other Cultures

Oudh is traditionally used in various aspects of Middle Eastern culture, from the creation of high-end perfumes to the crafting of exquisite incense for religious and ceremonial purposes. The scent of Oudh is often associated with hospitality and warmth, with many Middle Eastern households using it to welcome guests, creating an atmosphere of opulence and respect.

In our related article, Oudh - The Priceless Fragrance of Legends, you can learn more about oudh and watch the Scent From Heaven documentary. It is is time well spent, in learning about how oudh is a cultural staple of Middle Eastern culture.

Its use in perfumery and the appreciation of Oudh is a cultural art form, reflecting a deep connection to the land and the natural world. In many ways, Oudh encapsulates the essence of Middle Eastern culture, evoking the region’s rich history, traditions, and timeless elegance.

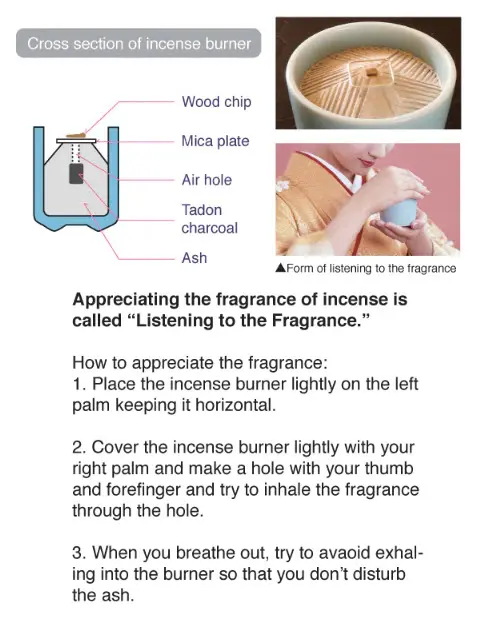

The Preferred Method for Burning Resinous Incense

When it comes to burning resinous incense, like the precious Oudh, an ancient practice that transcends borders and centuries, the choice of method can significantly impact the experience.

To preserve the delicate aromas and ensure a more controlled release of fragrances, many connoisseurs recommend using a mica plate instead of placing the resin directly on coals. Mica, a natural mineral known for its excellent heat resistance, provides a stable and even surface for the incense.

This is the method that kodo is practiced. A mica plate is placed on top of smoldering coals, and the incense on top of the mica plate, separating it from the coals and being burned. This way, it gives off its natural fragrance in a subtle way.

Kodo Preparation

In the art of Kodo, the preparation involves using a traditional Kodo cup, a censer filled with white rice ash, charcoal, and a delicate mica plate to enhance the aromatic experience.

- Begin by filling the kodo cup, also known as the Censer, with white rice ash until it’s about two-thirds full.

- Take a piece of charcoal and heat it until it turns a uniform grayish-white.

- Fluff the ash to ensure it’s not densely compacted.

- Position the heated charcoal at the center of the censer, directly on top of the ash.

- Gently push the charcoal into the ash so that it’s anchored about halfway down in the cup.

- Create a mound or cone shape on top of the charcoal by covering it with ash.

- Using an ash press or a butter knife, lightly tamp and compress the ash to form a neat cone.

- With a metal chopstick or skewer, carefully craft an air hole leading to the charcoal.

- Delicately rest the mica plate atop the air hole and apply gentle pressure.

- Finally, place a piece of fragrant material, such as Jinkoh, Sandalwood, Aloeswood, or other loose incense, onto the mica plate.

This method not only enhances the longevity of the incense but also allows for a more harmonious and nuanced olfactory journey, making it the preferred choice for those who seek to savor every aromatic note.

Videos: Kodo Ritual and Luxury Incense

Aloeswood is cut into small rice grain sized chips, as small pieces best extract the aromatic elements.

12 minute summary of the two-hour long Kodo ceremony. Kodo is more about the rhythm of spaces rather than the activity itself.

Japanese Incense – Home Luxury

👉Read more: Oudh - The Priceless Fragrance of Legends

Highly sought-after and precious incense that is more valuable than gold by weight